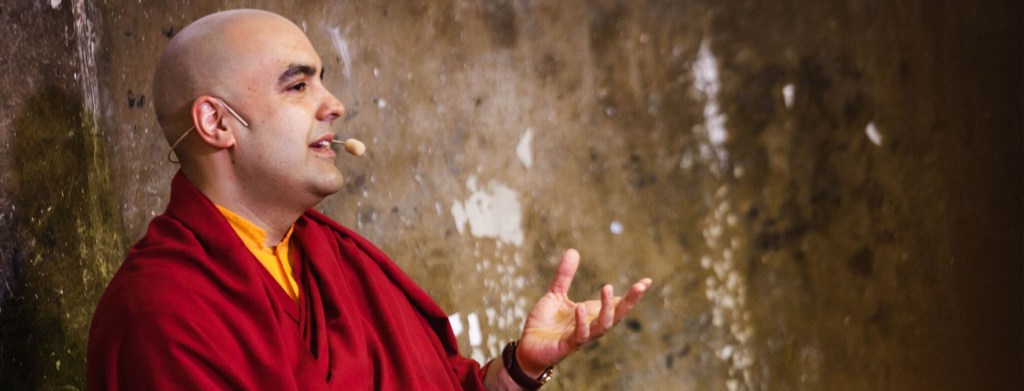

A Monk’s Guide to Happiness

In June 2009 I emerged from a meditation retreat that had lasted four years. It was an intensive programme alongside 20 other monks, in a remote old farmhouse on the Isle of Arran in Scotland. We were completely cut off from the outside world, with no phones, Internet or newspapers. Food was brought in by a caretaker who lived outside the walls of the retreat and we had a strict schedule of between 12 and 14 hours’ meditation per day, mostly practised alone in our rooms. This programme went on in the same way every day for four years. We were allowed to talk a little to each other at mealtimes or in the short breaks between sessions, but things intensified in the second year, when we took a vow of silence for five months.

I had never attempted such a long retreat before, and it was incredibly hard. I remember thinking it was like having open heart surgery with no anaesthetic: you’re backed into the corner with your most painful thoughts and feelings, with no distraction or escape. This type of retreat is a radical method of meditation training, found in many Tibetan Buddhist monasteries. The completely immersive environment and intense schedule of long meditation sessions push the meditator to make friends with their own mind. At times, it was the unhappiest period of my life, yet in the end it taught me a lot about happiness. I learned that happiness is a choice, and something that we can tap into within ourselves.

The other monks and I had no idea what was happening in the outside world. Several things occurred during this period which have impacted upon our culture, including game-changing technologies such as the launch and widespread use of the iPhone, the arrival of YouTube, Twitter and Facebook, as well as major historical events such as the election of President Obama, the financial crisis and the execution of Saddam Hussein. Our retreat teacher would come in to check on us every few months, and did hint at some pieces of news: we were told there was this ‘thing called Facebook where people ask you to be friends with them, and you feel too guilty to say no’; hearing this, we simply stared in wide-eyed wonder.

Emerging from the retreat, I was also struck by how people’s use of instant gratification as a means of feeling ‘happy’ had reached new heights and how dissatisfied they were still feeling. As I started to interact with things, I got a strong sense that meditation was exactly what the world needed now, and not as a luxury but as a matter of survival. I became passionate about the pressing question of true, lasting happiness and what that really meant. So with a deeper sense of commitment, I immersed myself in teaching meditation in diverse environments, such as schools, universities, hospitals, drug rehabilitation centres and prisons, as well as in global technology companies and numerous highly stressed workplaces.

Read more about Gelong Thubten’s experiences in his guide to happiness here.